Here are the top 10+2 conferences for Natural Language Processing:

- ACL: Association for Computational Linguistics

- EMNLP: Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing

- NAACL: North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics

- EACL: European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics

- COLING: International Conference on Computational Linguistics

- CoNLL: Conference on Natural Language Learning

- SIGIR: Special Interest Group on Information Retrieval

- AAAI: Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence

- ICML: International Conference on Machine Learning

- ICDM: International Conference on Data Mining

- Journal of Computational Linguistics

- Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics

- Journal of Information Retrieval

- Journal of Machine Learning

- LREC: Language Resources and Evaluation*

- NeurIPS: Neural Information Processing Systems*

Updated, December 2018: I’ve included LREC & NeurIPS as conferences that often feature good NLP, but can carry varied quality due to lack of peer review or lack of focus on NLP.

Like every engineering field, there are top conferences for Natural Language Processing (NLP) with around 20% acceptance rates and there are also places that accept every paper. That means there is a lot of junk out there. With the exception of a Quora response about NLP, I couldn’t find much on the web about what counts as good venue when I was asked this week. A lot of this is the implicit knowledge of people within the field but is a little opaque to outsiders: some of the best conferences don’t do a whole lot in the way of promotion, as everyone in the field already recognizes them as the leaders.

So for people outside the field who are trying to navigate what counts in NLP, I thought I would try to share something a little more comprehensive. To keep it simple, in Natural Language Processing you really only need to look at these six conferences:

- ACL: Association for Computational Linguistics

EMNLP: Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing

NAACL: North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics

EACL: European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics

COLING: International Conference on Computational Linguistics

CoNLL: Conference on Natural Language Learning

You could also look at top conferences in the related fields of Information Retrieval, Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Data Mining:

- SIGIR: Special Interest Group on Information Retrieval

AAAI: Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence

ICML: International Conference on Machine Learning

ICDM: International Conference on Data Mining

There are also a smaller number of relevant journals:

- Journal of Computational Linguistics

Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics

Journal of Information Retrieval

Journal of Machine Learning

So here’s a simple solution:

- If the paper is from the main conference at one of these venues or is in one of the journals, read it. If not, ignore it. The same goes for where should try to publish any paper that you believe is groundbreaking research.

Exceptions and exceptional: what else to look for

This was a simplification and the long answer is much more complicated. There are also perfectly good reasons to publish work about Natural Language Processing elsewhere: most of my publications and presentations have not been at these venues.

To help you navigate the differences, here are some additional things to take into account. Most of this is widespread knowledge with NLP, but some is a little subjective and results from my own experience:

1. READ: Conferences and Journals

Conferences are king. If you are looking at papers, there is a big difference between conferences and workshops. Make sure that the papers are from the main conference, not associated workshops. The top conferences in engineering are often better than the top journals (unlike most sciences). This is primarily because of the fast turnaround, which attracts more researchers. Journal standards are still high, and are more often for articles that cover more than can be squeezed into a typical 8 or 10 page conference paper.

… and if anyone can tell me the difference between a ‘workshop’ and a ‘symposium’, please let me know.

Be careful with adjacent conferences. NeurIPS has a long history of accepting substandard NLP papers because the conference was focused purely on Neural Architectures and evaluated on the Machine Learning algorithms. But there are some great NLP papers there, too. Look for papers where the authors have also published the results in NLP-focused publications.

2. SKIP: Workshops about an application area

Workshops about the application of NLP to a given area are mainly for people who work in similar subfields or applications to share their research and look for opportunities to collaborate. They are also great for young researchers to get their first publications. Having a focused subject area also serves to entice other researchers to the application area.

For example, I was on the program committee for the Workshop on Language Processing and Crisis Information 2013 at IJCNLP. It was a great workshop with some solid papers and generated interest among other NLP researchers who might think about applying their skills to this area. So overall, it fulfilled its purpose. But most of the submitted papers were accepted, so there is no guarantee that the NLP components were carefully reviewed. For this kind of work, look out for papers by the same authors in the leading venues in the years following.

3. READ: Workshops that focus on an NLP subfield

For example, I published a paper on Named Entity Recognition for disaster response at the 4th Named Entities Workshop (NEWS), which was alongside the ACL conference in 2012:

Munro, Robert and Christopher Manning. 2012. Accurate Unsupervised Joint Named-Entity Extraction From Unaligned Parallel Text. The 4th Named Entities Workshop (NEWS), Jeju, Korea.

I tend to trust workshops about subfields more than workshops about areas of applications. You can guarantee that the reviewers of our paper did know a lot about the particular subfield of “Named Entity Recognition”. But it would generally be easier to get accepted than to the main conference, so the quality can still be lower at workshops like these. I’m not sure how competitive NEWS was, but more popular subfields like machine translation have high quality. For example, the Workshop on Statistical Machine Translation has papers that I would trust as well-reviewed work in machine translation, equivalent to most published in the main conferences.

4. SKIP: Keynotes and invited talks

If you are invited, it’s (obviously) not blind peer-review. I will use an example of mine that doesn’t count:

Munro, Robert. 2010. Crowdsourced translation for emergency response in Haiti: the global collaboration of local knowledge. (Keynote) AMTA Workshop on Collaborative Crowdsourcing for Translation. Denver, Colorado.

Keynotes are a great way for people to go outside the normal constraints of academia and talk about big picture and strategic issues. They are also a great way for people to summarize a large body of past work. But the content of this paper was not subject to blind review, so you shouldn’t treat this paper of mine as peer-reviewed, or any other invited paper.

5. READ: Short papers at top conferences

Some conferences allow short papers, typically 4 pages. A short paper at a good conference is almost always better than a long paper at a workshop or lesser conference. Most often, a short paper means it was rejected as a full paper and resubmitted, so it is not necessarily up to the standard of full papers at the same conference, but in other cases 4 pages is all you need, and so some conferences will even ask people to submit long and short papers at the same time to ensure deliberate, targeted short papers rather than cut-down longer ones. Look at the ‘call for papers’ page for the conference to determine the exact status of a short paper.

6. SKIP: Conferences that are reviewed by abstract (or not at all)

In the humanities, conference papers are not typically fully reviewed and journals are more important (this is typical pretty much everywhere outside of engineering).

In NLP, an example is the LREC conferences where the papers are reviewed by abstract only and then they publish that abstract without further revision. LREC is the best conference to find information about resources for NLP and the place for people who create language resources to come together. But the papers are not peer-reviewed: look for the NLP-related content to also be published elsewhere, and only then trust the papers in LREC for their NLP content

7. READ: PhD dissertations from top institutions/advisors

Doctoral dissertations can count as peer-reviewed work, but the variation is as great as that across all papers. It helps if the dissertation is awarded by a top university, but ultimately you want to be sure about expertise in the given area. Look to see who was on the review committee, and then see how established these researchers are:

http://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=search_authors&hl=en&mauthors=label:natural_language_processing

Does the PhD committee consist of the top researchers? In that case, you can count it. A good PhD will also have several chapters published at top NLP conferences.

8. SKIP: Conferences & journals outside the field

This is where we find some of the worst papers. If reviewers don’t have a background in NLP, then they are more likely to let papers slip through with erroneous or misleading information. Even journals like Nature can let through bad NLP: see Mark Liberman’s review of “Languages cool as they expand” in Language Log (a must-read blog about language, even if not a peer-reviewed venue).

Another example is ISCRAM: Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management. On multiple occasions I have seen my own work distorted there. In one paper, researchers misrepresented complicated language-independent research of mine to wrongly quote us as saying that English-centric research did apply to other languages—a misquote that allowed them to skip building the (hardest) 90% of the research. In another paper, researchers I had been corresponding with failed to report that their system didn’t beat a naive baseline. That means they presented a negative result as positive novel research that they encouraged others to follow.

I’m sure that these aren’t the only two papers at ISCRAM that are trying to promote systems that have already been proven not to work. By publishing papers that are obviously false (to those of us who do know about NLP), conferences like ISCRAM are more likely to drive serious researchers away from topics like disaster response. This doesn’t work out well for anyone. I am sure the conference organizers would like to host quality research, but I recommend avoiding stand-alone conferences outside the field, both as a researcher and a reader.

9. READ: Papers with many citations

Citations can be a good indicator of a paper’s importance, but it’s tricky. For example, the subfield of ‘BioNLP’ overlaps with the field of Biology, which has tons more researchers than NLP and therefore more people who could cite a paper. Sometimes, even a technical report (a non-reviewed paper) can be influential:

Winograd, Terry (1971). Procedures as a representation for data in a computer program for understanding natural language. Technical Report, MIT.

Many foundational papers are likely to be similar, as they are often inventing the scientific field, and so there were not yet conferences dedicated to that field. As a rule of thumb, 1000 or more citations for a paper in NLP means that it is probably quality research, especially if many of those citations are also from papers in top venues.

10. SKIP: book chapters

If the paper is a book chapter, then it is most likely a workshop paper in disguise. Many lesser workshops and conferences in engineering will publish the proceedings of the conference as a book. This isn’t necessarily deceptive—it stems from before most papers were published online and meant it was an easy way to bundle papers for distribution. In most other cases, book chapters will be invited, and therefore not subject to blind peer-review. The research will also be published in leading venues in addition to the chapter if it is quality work.

11. READ: Textbooks from leading researchers

This is a tough one: anyone can publish a book at any time and call it what they want, but the most popular textbooks do tend to come from the leading researchers. I would suggest that you can go by author: if they have published at the leading venues listed above, then chances are the textbook is also good quality. The number of citations will also be a useful indicator.

12. SKIP: Academic papers that talk about deployable systems

We need academics to push the boundaries of the science, a rare and vital skill, rather than having our best and brightest produce substandard software—something the world has enough of.

Unless the researcher is at a large company with an established R&D team focused on NLP, like Microsoft, Google or IBM, they are not going to produce software that can be used in industry. Machine learning at scale is extremely complicated and builds on many software development skills about operations and monitoring that are not related to Natural Language Processing, and therefore outside academic skill sets.

13. READ: Anything from your favorite researcher

We have all been burned by “reviewer #3″ and seen research that we believed was good get rejected. Sometimes, a good researcher will simply submit this research to a lesser venue in order to share it with the community before moving on to new projects. If you already know that a researcher produces quality work, then look for some gems in less prestigious locations.

Some examples (of my own)

I wrote this post after receiving a few emails recently asking which papers of mine are best to read and what counts as a good venue for Natural Language Processing. It turned into a longer discussion than I expected as I went back and forth over the complexities of why it is important where something is published, and then all the exceptions above.

The specific question was about Natural Language Processing for social good. So I will use my own papers as an example, partially for convenience and partially because I don’t want single other people’s papers that “don’t count”.

1. Subword Variation in Text Message Classification.

Munro, Robert and Christopher Manning. 2010. Subword Variation in Text Message Classification. Annual Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (NAACL 2010), Los Angeles, CA.

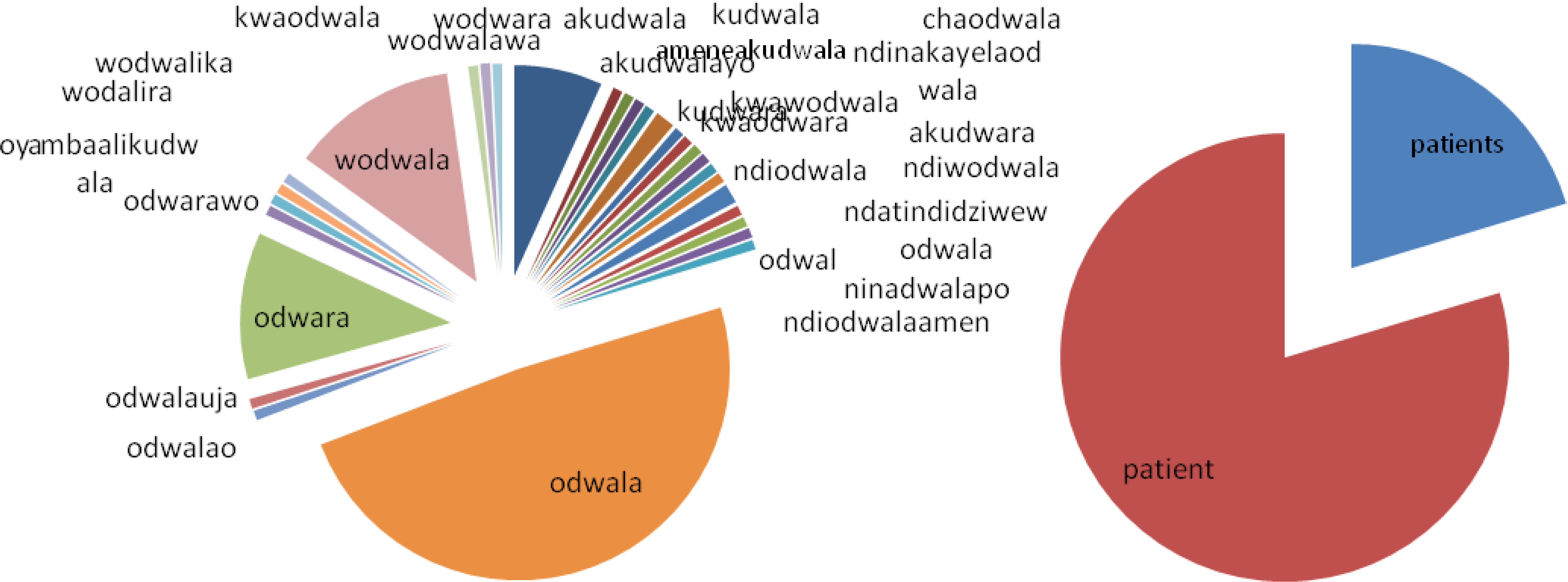

This paper looked at messages sent between health workers in Malawi, and compared NLP techniques for English and the Chichewa language. The 600 Chichewa messages have more than 40 spellings for the word odwala (‘patient’), with most appearing just once. This is problematic for approaches to Natural Language Processing, which assume the level of standardization that is found in formal written English. However, since the variation is linguistically predictable, it follows patterns that can be modeled with unsupervised machine learning, showing that you can build systems that work across languages, but not if they simply use keywords.

Why it counts: NAACL is one of the leading NLP venues. This was the work that kicked off my Natural Language Processing and Crowdsourcing for social good work. I completed this work in 2009, and it was what led to me running the crowdsourced response to Haiti in 2010 (next paper), where I pushed for crowdsourcing, not NLP, to be used for critical reports and translation, although we did end up using both.

Figure 1: Spellings of ‘patient’ in Chichewa and English. This shows the inherent variation in spelling that is typical of most of the world’s languages and the need to model this variation for accurate NLP.

2. Crowdsourcing and the Crisis-Affected Community

Munro, Robert. 2013. Crowdsourcing and the Crisis-Affected Community: lessons learned and looking forward from Mission 4636. Journal of Information Retrieval 16(2):210-266. Springer.

This was an after-action review for the crowdsourced response to the earthquake in Haiti. It was (and still is) the largest use of crowdsourcing for humanitarian response. This paper shows that they key to successful information processing for humanitarian response was the engagement of the Haitian population.

Why it counts: The Journal of Information Retrieval is one of the leading journals in the field. I won’t draw a hard boundary between different kinds of language technologies and or go into the differences here. It is worth noting that some researchers distinguish information retrieval from NLP, crowdsourcing is still finding its place, and there are other related fields like speech recognition. Regarding the date, note the publish date is 2013, although it was mostly written in 2010 and submitted to the journal in 2011. While conferences have a turnaround of a few months, journals can often take a year or two to go from review to publication.

3. Subword and spatiotemporal models for identifying actionable information in Haitian Kreyol.

Munro, Robert. 2011. Subword and spatiotemporal models for identifying actionable information in Haitian Kreyol. Fifteenth Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning (CoNLL 2011), Portland.

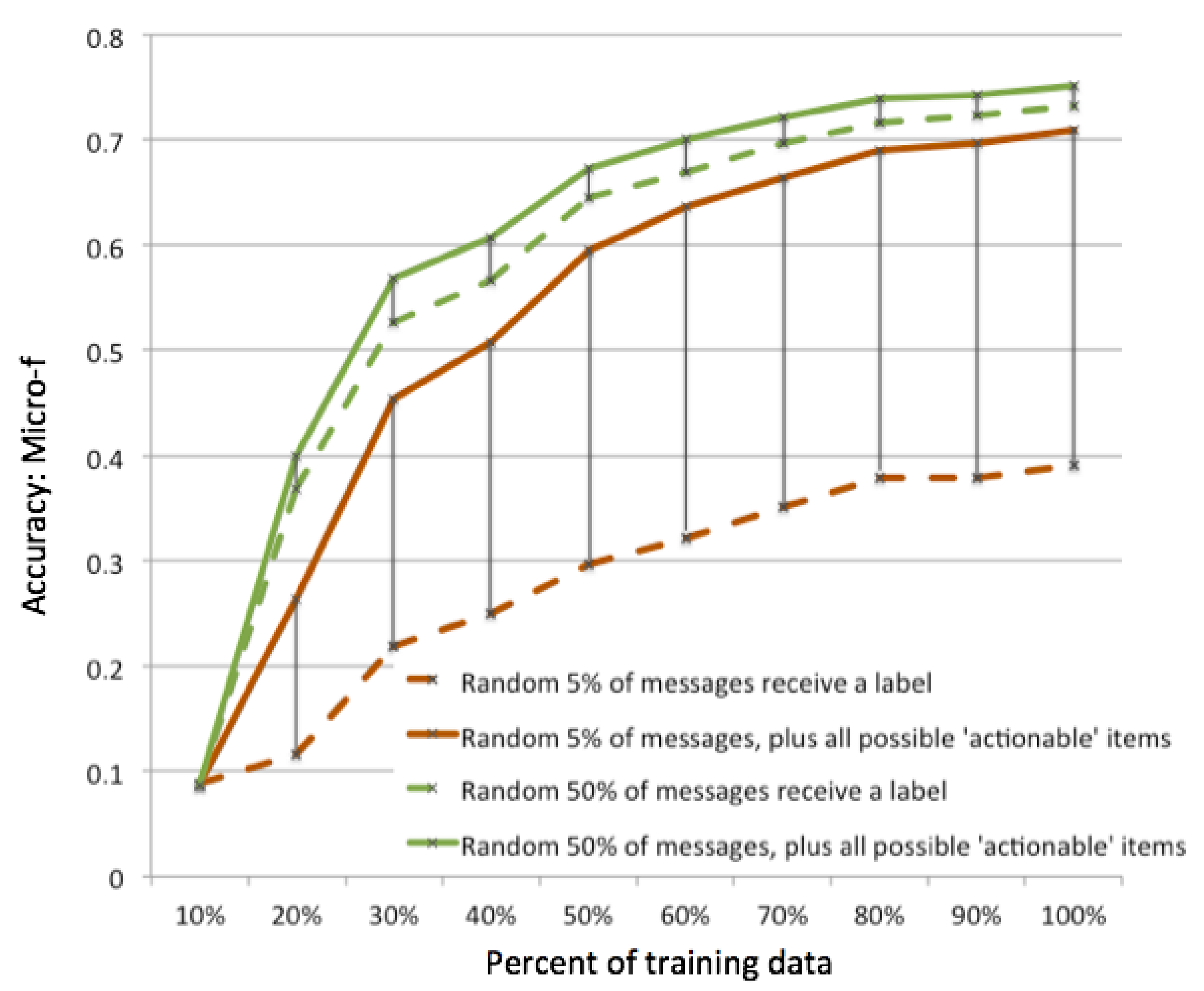

This was the first study that looked at scalable natural language processing in a disaster context, considering the possibility of building systems that could extract useful information for disaster response from text messages and from social media. The research models non-linguistic data including temporal and geographic information for greater accuracy, and was expanded upon in my dissertation to explicitly look at reducing the human cost in continually evolving environments.

Why it counts: CoNLL is one of the leading NLP venues. It is competitive—the acceptance rate was 16% in 2011—but it is also smaller than ACL, so it is less prestigious. This research was a little outside of the norm for NLP research: focus on a low resource language; streaming machine-learning architecture; integration with non-linguistic data. This makes a top-tier publication less likely, not necessarily because of favoritism for certain topics, but because the reviewers will have less of a grounding from which to compare the results: most NLP papers are incremental progress on well-known problem sets. For a more novel/unusual paper to be accepted by peer-review, clearly established baselines need to be set within the paper.

Figure 2: Active learning for identifying actionable information with minimal human input, showing that you can increase the efficiency of the human workforce by a factor of 10 while achieving almost the same accuracy.

4. Short message communications: users, topics, and in-language processing.

Munro, Robert and Christopher Manning. 2012. Short message communications: users, topics, and in-language processing. Second Annual Symposium on Computing for Development (ACM DEV 2012), Atlanta.

This paper was a deeper comparison of languages and methods of communication following natural disasters, (e.g., text messaging/SMS vs. Twitter), looking at Haitian Kreyol and Urdu in addition to English. It was the first time that social media had been compared to private reports directly from the crisis-affected population. The study found that social media was much more ambiguous and prone to misinformation, and that the information mapped poorly to events on the ground, although a broad variety of use cases are attested in all reporting channels.

Why it does not count: ACM DEV is not a mainstream NLP venue, so this paper was not necessarily reviewed by top NLP researchers or published in a competitive location. The goal of submitting this paper to the ACM DEV conference was to get feedback from people in social development and to let people in disaster response circles know that they should be concentrating information processing efforts on direct reporting, not open social media.

Why it does count: For a paper like this, the NLP would also need to be reviewed elsewhere to be considered leading research. In this case, the research was part of my dissertation so the NLP counts there. This is good advice in general: if there is a publication at an out-of-band venue, you can evaluate the quality by seeing if the NLP components are also published at a top-tier venue.

5. Tracking Epidemics with Natural Language Processing and Crowdsourcing.

Munro, Robert, Lucky Gunasekara, Stephanie Nevins, Lalith Polepeddi and Evan Rosen. 2012. Tracking Epidemics with Natural Language Processing and Crowdsourcing. Spring Symposium for Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), Stanford.

This paper presented work on what was likely the largest use of natural language processing and crowdsourcing for social good ever, processing billions of data points each day in more than a dozen languages. In addition to this paper it was presented to the UN General Assembly on “Big Data and Global Development” and a number of high-visibility venues. I wrote this about on my personal blog: Tracking Epidemics with Natural Language Processing and Crowdsourcing.

Why it does not count: See the ‘Symposium’ part above? This means that our paper was not in the main AAAI conference. So in this case, it doesn’t count as a top paper. Unlike the ACM DEV paper above, we never got around to submitting the work to a more competitive venue. It’s not that we thought that the work was not worthy, it’s just that our focus moved on and we didn’t put resources into it. So, sadly, despite the publicity around this project and my belief that it was groundbreaking research from an amazing team, there was never the guarantee that came from blind peer review by the leaders of the field.

Other lists and things I missed

While I tried to make a list of publication venues that was objective, there are some that I simply don’t know as much about, like IJCNLP International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing and the new joint conference of computational semantics, SEM*. You could make an argument that they are as competitive as some of the conferences I listed above and only lack the current prestige for being a little newer.

There are also a few more general machine-learning/data-mining conferences that often have NLP papers: NIPS and KDD (NLP researchers, what do you think?) or ones more focused on related fields like speech recognition, such as Interspeech.

For ongoing resources, look for people creating lists of conference deadlines, like Joel Tetreault’s page. These will give you a good idea of what a researcher in the field thinks is important. Similarly, look for the ‘acceptance rates’ of conferences on aclweb.org. A low acceptance rate at a conference with many submission is typically a good indication of quality.

Finally, there are a number of organizations that will rank conferences for universities. For example CORE rates all conferences that I listed above as “A*” or “A”. These rankings are often used to directly determine funding, salary or job opportunities for academics.

Why it matters

Chances are, a paper in a top venue had been rejected once or twice and a lot of work has gone into ensuring rigorous results and novel research. If you have limited time or are suspicious about certain results or claims, peer-review is by far the best method to ensure quality. If you are looking to publish your paper, it is worth the extra time and effort. Papers at venues that are not listed here are not necessarily bad, it is just that they were not reviewed to a standard that ensures quality.

Please do comment if I have missed anything that you think is important!

Rob Munro