Why you should not use Twitter in a disaster

It’s safe to say that I know more about social media in disasters than pretty much anyone. I’ve helped run disaster response efforts utilizing social media in English, French, Haitian Kreyol, Urdu, Pashto, Spanish, Portuguese, German, Hindi, Sindhi, Arabic, Sudanese, Indonesian, Japanese, Korean, Italian, and more than a few other languages, across six continents and more countries than I can count. My PhD from Stanford was the first anywhere that looked at applying cutting edge Natural Language Processing to short social media communications in crisis response contexts globally. My company, Idibon, is currently working in social media for disaster analytics in a number of locations.

So I say the following with conviction and expertise:

- Do not use Twitter for reporting risks during a disaster.

It does more harm than good to share open information about at-risk populations. In every context that I have seen, the misinformation is more viral than the truth; people using social media rarely self-correct misinformation with the same virality; the information is often condensed to the point of being misleading through omission; and most of all, the world’s most at-risk people are being put in danger.

In my professional work, I have worked closely with crises-affected populations and as a result I have long been opposed to sharing information online about at-risks populations, and a vocal opponent to media organizations that do. But I am also hesitant to criticize the people who *do* share information when they are directly connected with the disaster. It’s not reasonable to expect people to act rationally.

Last week, I provided an example myself. So I’ll use my own error to point out the argument.

When it’s close to home

Last week, fires swept through my childhood home of the Blue Mountains in Australia. Family friends lost their homes, and from San Francisco I saw a stream of photos of familiar streets with an apocalypse of smoke hanging over them. It is the small things that make it so familiar: the cars on the left, the shape of the power poles, the style of houses and lawns. On Tuesday, I heard from my mother that she was evacuating her home to stay with family friends outside of the region.

It felt terrible to view the photos and videos as many people I know were leaving the town I grew up in as an inferno approached. It felt just as bad to be so far away at the time. I received the news of the evacuation on a day that was more than typically busy: I had meetings starting at breakfast and going past dinner; I was moderating a panel at the annual crowdsourcing conference; I was trying to remotely manage staff in-between. For the whole day, the safety of many of the most important people to me was in my mind, and I tweeted without thinking:

- @WWRob: my thoughts are with my family and friends evacuating the Blue Mountains today.

Despite my expertise, experience, and my vocal opposition to publishing risks about at-risk populations, when it was my hometown that was threatened, I made the mistakes that I warned against. I quickly deleted the tweet and the Facebook post that it had automated generated. Here’s why:

1. I was (potentially) contributing to misinformation. Nothing I said was untrue, but without the full context my tweet could have been interpreted as a full evacuation because the fire was expected to go through all inhabited areas, which wasn’t the case (see below). This is just the kind of ambiguity that is hardest for me to evaluate when running disaster response services, and I am annoyed that I repeated it.

2. I was misleading through omission. The risk to my parents’ home was small. The fire was only a few kilometers away for several days, but the prevailing wind and availability of fuel reduced their specific risk. People had been advised to evacuate by a certain time or not leave, primarily so that the roads remained free for emergency crews during the expected worst period (there are many places with only one road in an out, often narrow and winding). But it was also positive that many people stayed: many places were only at risk of spot-fires from embers, and it can help disaster response efforts when people are able to identify small spot-fires as quickly as possible. The subtleties of why people were being evacuated couldn’t be expressed in 140 characters.

3. It put my family’s home in danger. It wouldn’t be that difficult to figure out who my relatives in the area are and find their address. And I just announced to the world that their houses were empty, in a neighborhood where the emergency responders were sure to be busy elsewhere. There was no widespread looting, fortunately, but there were thefts of donations for fire victims already reported – I should have known better.

Cheap journalism and cheaper lives

Was I wrong to empathize, worry, and express my concern? No, or at least, if I was wrong, everyone else who reports their concerns on Twitter is less wrong, as they do not work with in the area. So I don’t blame individuals when they do express their fears under more duress and with less knowledge of the unintended outcomes.

Are traditional media who rely on social media for stories about disasters wrong? Maybe. In all my experience, I have never seen an example of social media being useful in disasters for collecting information from the population (‘situational awareness’). It is worth pursuing as a research topic, but not yet for response. From hundreds of millions of social media interactions that have been collected and analyzed during disasters, I have only seen one example of information going to responders via social media that definitively helped someone. Against that one positive case, I have seen dozens of confirmed examples of people being killed or going missing as a result. In the 2009 Mumbai hotel attacks, the terrorists used social media to identify and kill American and Jewish hostages. Mexican cartels have repeatedly used social media to identify and execute their perceived enemies. The majority of people tweeting in Tehran during the ‘Twitter Revolution’ are now unaccounted for, not because Twitter actually played an important role: the media declaring that Twitter was important put the spotlight on people who had no choice but to suffer the consequences.

Against so much death and hundreds of millions of tweets analyzed with little or no positive impact, the media then turns around and produces articles like this:

This article, published yesterday by Bruce Drake of Pew Research, is a dangerous lie. The article is a report on a different article that was also by the Pew Research center, which simply categorized how Twitter was used. Drake side-steps the finding that the most shared information was incorrect and adds this ridiculous title about a ‘lifeline’ which he seems to have invented for publicity. And it work – this lie was happily retweeted by people like Alex Howard who should know better. As is already well-known, NYC sent less than one tweet per day per social media staff member. When my company was helping FEMA run information processing following Sandy, I don’t remember much talk of social media at all.

These false reports about the importance of social media are encouraging more people to share information about at-risk populations online and will ultimately contribute to more difficult disaster response efforts with fewer people helped.

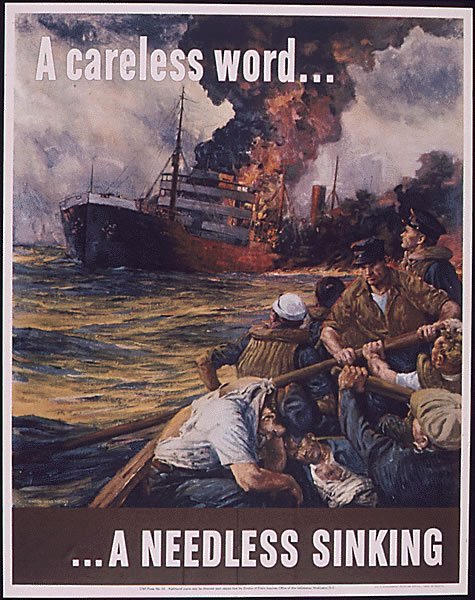

Loose lips

To separate out the functions of social media, there’s a strong argument to be made that emergency response organizations should use social media as a broadcast medium, as people consume news via social media, and use it to point people to the correct reporting channels. I first argued this in 2011: disaster response organizations should use social media to encourage the centralization of information. The recent Twitter Alerts project follows this advice. Twitter have (thankfully) ignored requests by media agencies to remove disaster-related hashtags from their API limits, and instead allowed professional response agencies to use their services to broadcast information.

But disaster response professionals and the media alike should stand against reporting sensitive information about disasters on social media. There’s nothing new in campaigning for safer information sharing, but where are calls for this? It is a natural compulsion to speak out about what worries us, but it is not natural to think of the implications of spreading information to such a wide audience. When I tweeted about the evacuation of my home town, it was in solidarity with the people that I knew there, but I didn’t think beyond these people when caught up in the moment. I share my mistake as a warning to others: we need to be pro-active in curbing the publication of information about at-risk individuals.

Robert Munro

@WWRob

October 29, 2013