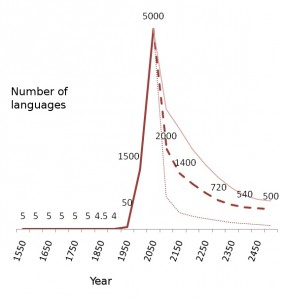

5,000 languages

Right now, you could have a conversation in one of about 5,000 languages. Just take out your phone and dial the right numbers. My rough estimates given celllphone adoption rates globally is that about three quarters of the world’s languages are accounted for by someone either having a phone in their pocket or access to one nearby.

Most people for most of history have spoken more than one language. Our brains are wired to prefer it: all else being equal, those who are brought up speaking more than one language will grow to greater wealth, intelligence and find it easier to learn further languages. While it varies greatly by geography, most people have spoken 2 to 3 languages throughout history and could probably have encountered 2 to 3 more each day (from neighboring language communities, traveling merchants etc). This averages to about 5 languages that a person could hear in a given day through pretty much all of history. On the back of industrialization this likely dipped as we saw large monolingual societies for the first time, although not enough to drop the average across the world by more than 1 language at most.Enter the two-way radio and telephone. All of a sudden people had the potential to communicate with hundreds of different language groups, especially as international calls became increasingly possible through the 20th century. But this technology was shared by a relatively small number of the world’s population: the overall average would not have risen to more than about 50 languages.

Enter the cellphone. Everything changes. Within a handful of years, we have become able to directly reach almost every language. Some language communities still don’t have cellphone coverage (or cellphones), but for many of them there will be speakers working in towns or cities that do. For the majority of these our entire scientific knowledge will consist of little more than decades-old sketch-grammars by hippy-linguists or missionaries. This 5,000 is also well in excess of the number of language recordings contained in any leading language archive, like the Endangered Languages Archive or DoBeS (the archives are, of course, mandated to have richer recordings than scratchy cross-linguistic records of people saying “I think you have the wrong number”). The potential to engage the world’s linguistic population is huge. 50-90% of languages will not be spoken by the end of the century, hence the sharp drop-off in the graph. We are currently in a thin sliver of time where we will never again be so under-resourced to understand the languages around us, or have the opportunity to document so many.

Enter the Dragon. Technologies for speech recognition and dialogue have been around for a while (Dragon Talk’s website is a testament to this) but have never seen broad use until recently. Language loss is a side-effect of globalization. It is rarely in the economic interest of a language community to give up their more local languages as they pick up global ones, but linguistic and racial discrimination can make it seem this way and increasingly mobile populations can scatter speakers. However, the same processes of globalization have enabled large-scale digital recordings for the first time, while communication technologies have given language communities the option to continue speaking their languages at distance.

Will spoken dialogue technologies move into less resourced languages? It is difficult to say. Projects like Avaaj Otalo show promise. We know very little about so many of the languages that are now being spoken over cellphones, so needless to say we know even less about how or what people are actually communicating. Which makes for an exciting field to be working in.