A double rainbow, what is this meme?

My favorite Halloween costumes last weekend was a ‘double-rainbow’ – someone was cycling along simply wearing two rainbows, in reference to this video:

You might be the 20 millionth or so person to view it.

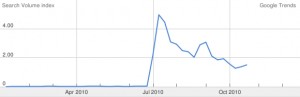

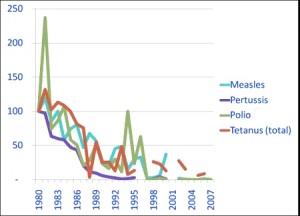

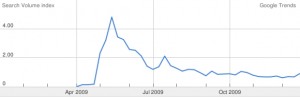

So apparently internet memes are a new genre of costume, but do they really go ‘viral’? Yes, it looks like they do. Or more accurately, they exhibit the same patterns of transmission as illnesses and violence, all of which are symptomatic of interactions within our social networks. I looked at the Google trends for the popularity of memes and they follow the same patterns of transmission: a sudden spike followed by a drop-off with smaller secondary spikes. You can see the same patterns in the graph of illnesses in Burundi (I cycled across Burundi at the end of this period and recall being told about recent health improvements.)

While Johnson and Johnson take care of health, Milroy and Milroy are responsible for the seminal work in linguistic innovation: Change, Social Network and Speaker Innovation. Linguistic practices within our strong networks of social ties determine how we use language to assert and negotiate our social identities, but it is our weak ties that introduce innovations. Illnesses are often spread the same way: you share colds with friends, but it’s that special post-spiritual-journey acquaintance who infects you with Bird Flu.

From the research in this area, it has become clear that most other linguistic innovations are more slowly acquired and persist longer than illnesses (which is good for both our ability to communicate and our general health). I recently saw Jessica Spencer demonstrate this in novel way using the NetLogo software to simulate human interactions, researching the acceptablity of the presence or absence of the copular in Creoles and English vernaculars (basically, whether it is more common to say something like “you good” verses “you are good” in a given language or speech community, and how this changes over time). The interactions of people within the simulation matched the observed distributions in a variety of populations, following an S-curve of slow initial uptake, followed by a rapid uptake by a large volume of the population, with a slow tail-off as the remaining hold-outs finally accept the change. The most comprehensive recent study (with plenty of graphs) is Celina Troutman, Brady Clark and Matthew Goldrick’s ‘‘Social networks and intraspeaker variation during periods of language change’. This pattern of innovation is widely observed across languages in both phonological and syntactic innovation.

But memes are taken up much more quickly than these other kinds of innovations, and are fairly quickly lost. We can still model them with network theory, just not the same ones that govern syntactic and phonological innovations. One of the biggest differences is that memes will spread through a community well after the initial adopters have moved on. There is probably someone who still greets people by saying ‘wazzzzup’, but I bet it isn’t the person who started it.

Our physical networks themselves occasionally show us this directly. When I am at the Caltrain station in San Francisco I often see an open wireless network called “Free Public WiFi”. I’ve seen it at airports, too, but have never successfully reached the Internet through it. I only recently found out why via a Tech Dirt article. This isn’t a free network, or a trap, it is actually a computer bug. When computers with certain versions of Window XP can’t find a network to connect to, they will automatically try to create a new ad hoc computer-to-computer network with the same name as the last one they connected to. (I’m sure that a computer-to-computer network is a ‘strong tie’ in the digital world). The computer will advertise this as an open network of its own, inviting others in. When those people join, even though they won’t actually get through to the internet, their own computers will record “Free Public WiFi” as the last network, and so this will spread as those people’s computers in turn try to create later ad hoc networks with the same name. Somewhere, at some point in time, someone must have been the patient zero who created the first “Free Public WiFi” network, but that person is now long gone, too, while our machines keep transmitting it.

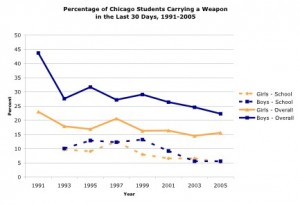

The most interesting correlation I’ve seen wasn’t directly related to language, it was about the transmission of violence. Members of the Ceasefire organization act as violence interrupters, actively seeking out high-risk individuals to prevent one act of violence propagating. On a recent visit to Chicago I met some of them: they obviously have the respect of the neighborhoods they work in. Their interpersonal success relies on strong social ties and so the interrupters are from the communities they serve and build up trusted relationships over time. The innovation of analyzing violence using transmission models comes from their founder, Gary Slutkin, for one simple reason: he is a former epidemiologist. He saw that patterns of transmission for violence matched the patterns of transmission for illnesses, and had the insight to treat them the same way – not as a direct socioeconomic problem, but as a transmission problem. They have been incredibly successful, reducing gun-related violence to zero in many of the neighborhoods they work in (for more on this, see Alex Kotlowitz’s NYT article ‘Blocking the Transmission of Violence‘).

So why look at patterns of distributions for linguistic innovation, memes especially? We talk to each other more than shoot, stab or transmit illnesses to one another. We can make predictions about one from observing the other and language may be the richest source of information. Watching memes spread across the internet is one of the cleanest and most detailed ways to observe social interaction at scale, and in turn can teach us about the nature of wide-spread transmission, be it illness, violence or any other transmittable condition. So go ahead and read that email from a friend saying ‘watch this hilarious video!’ – you might contribute to science.