I witnessed the birth of Emoji, and the short story is it almost didn’t happen. There was a long debate within Unicode about whether emoji constituted “language” that deserved to be represented alongside other characters. At the same time, Unicode was deciding whether or not to include characters invented by Isaac Newton, and used only once in all of history. It was interesting debate to observe both debates side by side.

Visualizing language is complicated. When we look at other symbols in language, it gets messy very quickly. As I have said before, I believe that Unicode is the most sophisticated visualization framework, ever. The characters render across phones, tablets and computers, globally. The characters are as intelligible on a tiny phone display as they are on the giant screens in stadiums.

It is easy to forget that the Unicode standard did just not appear on our devices by magic. It is the result of a small number of very smart people. If you look at http://unicode-table.com/, every ordering of charters and mapping to binary forms was a conscious decision. For a short time, I was a liaison to the Unicode Consortium, which is the organization that decides on the standard for gets to officially become a character in digital communications. My influence on the current standard is near zero, and I was mainly a passive observer on email chains where many decisions were made. However, I was witness to when Japanese ‘emoji’ were being added to the standard. This taught me how complicated and tense the process could be.

Emoji are picture characters that are particularly popular in Japan, especially among teenagers using phones. In the last few years they are becoming more widespread. Some examples that should display in your browser are: ⚔⚘☃☂.

As Wikipedia puts it, “[the addition of Emoji] went through a long series of commenting by members of the Unicode Consortium and national standardization bodies of various countries”.

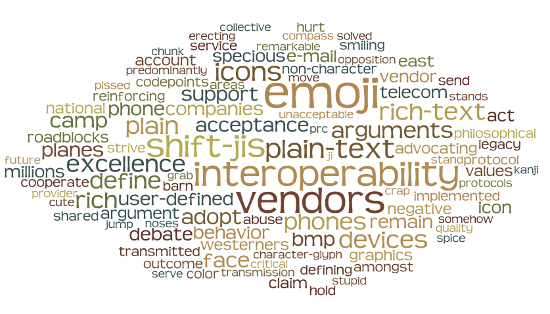

This is true, but “a long series of commenting” fails to capture the intensity of the actual debate. I took a few hundreds emails sent on Unicode mailing list about emoji, and compared them to emails on the list from the same period that were not about emoji. So, to get very meta, I created a language visualization of the discussions around emoji’s inclusion in the Unicode standard. Here are the words that were most indicative of the conversations about emoji vs. other topics (using point-wise mutual information):

“Specious”, “stupid”, “abuse”. It’s not surprisingly that the word ‘emoji’ was popular in the discussions, but clearly there was blood on the walls in the debate about whether cute icons should be considered language.

Isaac Newton’s notebooks were being encoded at the same time. I attend the meeting where the Unicode standards for Newton’s symbols were debated, fittingly under the biggest apple possible: Apple’s headquarters. There was one particular symbol that occurred only once: a handwritten scrawl that probably related to an element and/or valence, but the meaning was lost in time. The final standard and symbols can be seen at the The Chymistry of Isaac Newton.

Compare the debate around emoji, used by millions of people daily, to the debate around a symbol of unknown meaning that occurred exactly once in human history. And that debate was…

… crickets. There was no argument at all. The only debate was whether this one mystery symbol was truly unique or a variant representation of another symbol. For some reason, it held higher status than millions of messages sent each day by teenagers, at least in terms of a standard, but it was difficult to pin down exactly whypeople have such strong, and conflicting, views about how to best represent language.

Robert Munro

July 2014